controversy

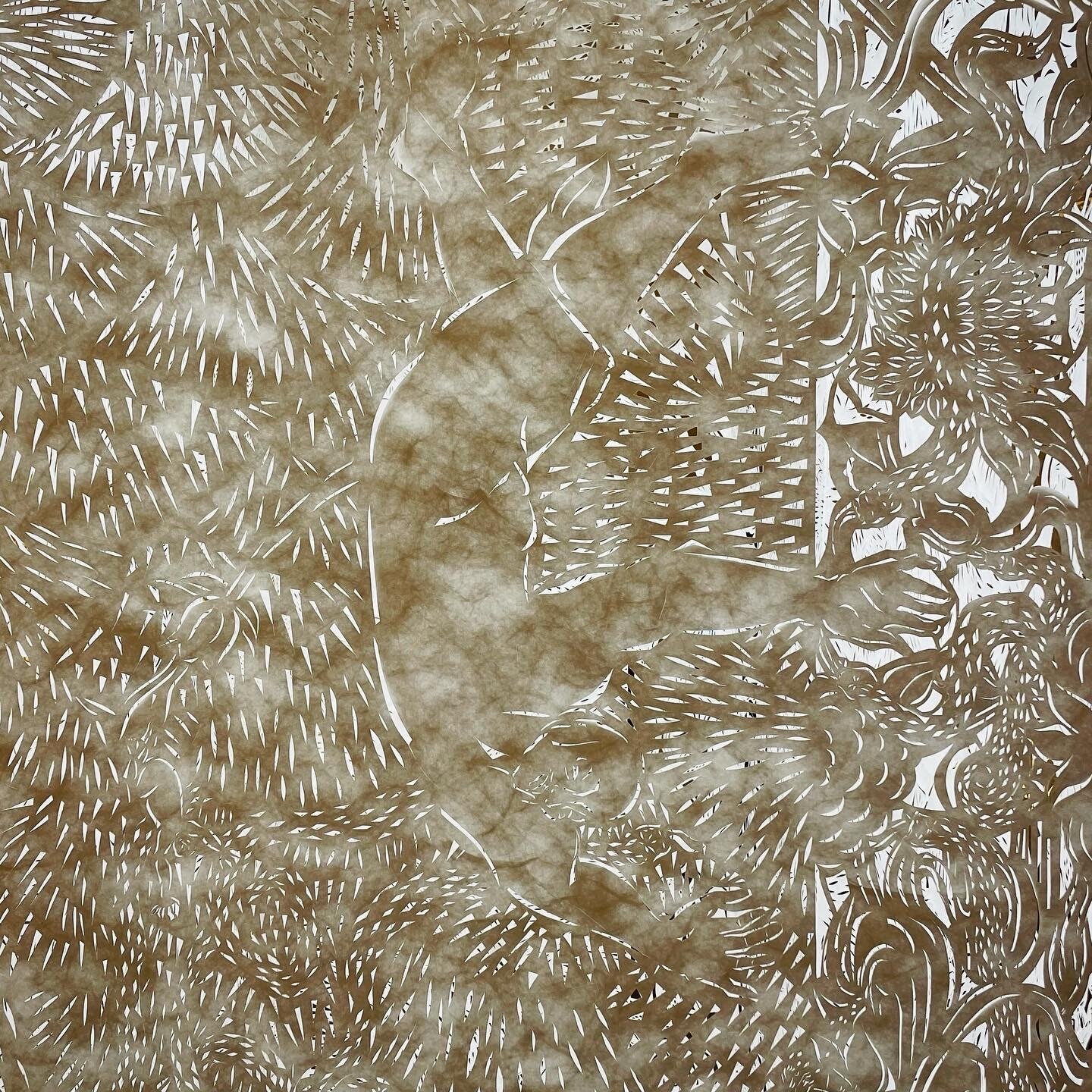

Detail of Barbara Earl Thomas, “Bodies: Falling in the Matrix.” Photo taken at the Seattle Art Museum by the author.

This week’s most salacious scandal came from the world of [gasp] professional sports. I know, right? Can you believe it? Is it a National Coming Out Day miracle? As the New York Times reported, the head coach of the Las Vegas Raiders resigned after a trove of his emails surfaced, revealing that Jon Gruden “had casually and frequently unleashed misogynistic and homophobic language over several years to denigrate people around the game and to mock some of the league's momentous changes.” Soon after the details were reported, Gruden announced his resignation on Twitter. Like a good twit.

“I have resigned as Head Coach of the Las Vegas Raiders. I love the Raiders and do not want to be a distraction. Thank you to all the players, coaches, staff, and fans of Raider Nation. I’m sorry, I never meant to hurt anyone.”

Gruden is already the target of all sorts of vitriol. While I typically avoid adding fuel to fires, especially those raging among the cancellers of culture, a couple of aspects of this scenario have rattled me. I won’t presume to speak for people who are offended by his derisive use of the word “pussy,” denouncement of women referees, or his habit of swapping photos of women with his buds. I won’t try to unpack his resistance to politically engaged players or his defense that he “never had a blade of racism in” him. I won’t try to diagnose the toxicity that leaks from the intersection of white, cisgender, and heterosexual identities and that bolsters the confidence of people like Gruden who consider their actions unquestionable, their power undeniable, and their privilege entitled. The folx whom those arrows wound can respond from their own vantage points and let us all know how Gruden failed and how we can all do better. I will, however, sit with two things that touch my own experience: his use of the word “faggot,” and the closing line of his resignation, “I’m sorry, I never meant to hurt anyone.”

The first time the word faggot was hurled directly at me was my first day of high school. After another student grabbed my collar and pushed me against the wall of a stairwell, he spit the word in my face and then walked away. I was one of 1,500 at an all-boys Catholic school with such a big sports program that nearly every academic department included coaches who needed a class or two on their contract to round up coaching duties and justify a full salary. My chemistry teacher was the head basketball coach (and because of his public mockery of an already vulnerable and targeted student, I just stopped paying attention to anything he said after I passed our first test on the periodic table). My economics teacher (who spent the first 15 minutes of class updating us with how his stock portfolio was doing) was an assistant football coach. Yeah, it was a great learning environment for a young musical theater aficionado like me.

“In the emails, Gruden called the league’s commissioner, Roger Goodell, a ‘faggot’ and a ‘clueless anti football pussy’ and said that Goodell should not have pressured Jeff Fisher, then the coach of the Rams, to draft ‘queers,’ a reference to Michael Sam, a gay player chosen by the team in 2014.”

À la Carrie Bradshaw, I couldn’t help but wonder, Did he work at my high school? While I was initially unsurprised (ooh, someone in the NFL is caught for being a Grade A jackass...and apologies to the jackass community if the metaphor offends any of donkeykind), I got stuck on the way reporters in the Times and on NPR consistently characterized his offenses as “homophobic.” Phobic? What is he afraid of? As a word, “homophobia” is wildly insufficient to capture the story it needs to tell. Whether it’s effected by an NFL coach or some random asshole in a school stairwell, homophobia points to aggression and violence against people because of their sexual identity, not fear of them. A semanticist might remind us that an irrational dislike or prejudice defines the term, calling it a “phobia” only affirms the notion that there is something to be feared. And that is some Jenny Jones “gay panic” defense bullshit.

Am I to be feared? I mean, I don’t think there’s anything to fear in me or my actions (unless you find yourself in a trivia game that ignites my superhuman ability to quote Murder by Death, All About Eve, and The Golden Girls...in which case, make peace with your god and gird your loins). By treating it as a fear, we perpetuate the fine, American tradition of blaming the victims, and, instead of resolving the source of an aggressive prejudice, we leave the burden on queer shoulders. To attain some hint of equity, we’re expected to demonstrate that we’re harmless, that we’re useful, that we’re, you know, people. Deprived of civil rights and social acceptance, the dominant thrust of queer activism appeals to heterosexuals’ sense of humanity, to trigger their empathy. And when straight people come around to [I hate this word] tolerating or even embracing queer folx, they expect affirmation and applause, whether or not their recognition of our humanity translates to committed allyship and meaningful action.

This tension was brilliantly lampooned in “Homer’s Phobia,” an episode of The Simpsons in which Homer distances himself from a family friend, voiced by John Waters, who is gay. With gay panic creeping up his spine, Homer takes Bart on a tour of hyper-hetero activities to negate any influence John might have. His last attempt to straighten up Bart is a trip to hunt bucks at Santa’s Village, but when the reindeer turn the tables and attack Homer, it’s John who saves the day and inspires in Homer a new-found respect for...John. “Well, Homer,” he responds, “I won your respect, and all I had to do was save your life. Now if every gay man could just do the same, you’d be set.”

In recent years, some have replaced “homophobia” with “heterosexism.” Stripped of any reference to fears, irrational or justified, heterosexism reflects the broad imposition of (heterosexual) assumptions that inhibits queer people’s lives, liberties, and pursuits of happiness. Unlike its predecessor, heterosexism clearly identifies the source of the problem: heterosexuals. I use this term frequently, and doing so helps me rewire the corners of my brain and my soul where internalized prejudice continues to haunt me. To quote Liz Lemon, “Words are the first step on the road to deeds!”

How does it haunt me, you ask? Before I walk into a room of heterosexual people, I tremble. I consciously calm my breathing and remind myself to speak as myself (not to summon a deeper, more masculine tone in my voice). I scan the room and look for clues that suggest friendliness and allyship. Except in predominantly queer spaces, I struggle to believe that I belong, that I deserve to be there, that my voice and my input are welcome. As I listen to people speak, strangers or familiars, I dig between the lines to excavate hidden messages or patterns, potential insults to anticipate and arrows for me to deflect. I map out the minefields of interactions that might bruise, cut, or break me. Among strangers, I quickly self-identify as a gay man, whether in subtle getures or explicit language, to forestall the inevitable remarks denigrating queer people, denigrating me. And, most diabolically, I actually believe that among heterosexual people, remarks denigrating queer people are inevitable.

Sure, these are my neuroses, but they spawned because of heterosexuals. All heterosexuals? Really? Yes, there are enlightened, loving, and justice-oriented straight people. Some of my best friends are straight. But, like global warming, my contemporaries didn’t start it, but they sure haven’t done enough to stop it. Real transformation begins with discrete, sustainable changes, choices that individual people make. So here’s a choice every one of us can make: let’s scrap “homophobia” from our vocabulary. Let’s avoid hiding behind clinical language like “heterosexism” and call it what it really is: hatred given form as discrimination, exclusion, psychological torture, or violence. Modify it as“anti-gay,” “anti-lesbian,” “anti-bisexual,” “anti-queer,” “anti-LGBTQIA+,” whatever applies, whichever group is being targeted, but call it hatred.

Mr. Flanagan was my 10th grade English teacher. Not a member of the coaching squads, he was an actual expert in English literature and language, a masterful teacher, and an effeminate and fabulous gay man. What he lacked in height and heft he made up in color and flourish. When we couldn’t make sense of the forms of modern poetry, distracted by the dispensing of conventional punctuation and grammar, he’d recite the poems with passion, with insight, and with joy. When we weren’t brave enough to articulate what we really heard or felt, he pushed us until someone would break through...and if no one did? He exploded. It was scintillating.

I have eaten

the plums

that were in the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

He read William Carlos Williams’ famous verses with intensity...slowing down to punctuate every word in the final stanza. Flanagan followed the last word with a long pause, giving every one of us enough time to figure out that this poem wasn’t actually about fruit. Then, suddenly, he slapped his desk and exclaimed, “WONDERFUL!” When he looked around for a response to his question about what the poet was really talking about, we resisted, embarrassed (though, whether we were embarrassed to talk about sex or about being able to understand poetry - that was different for each). “Anyone? Anyone?” We all avoided eye contact. “SEX! He’s talking about SEX!” he shouted with another slap of the desk. But, for me, the real insight revealed in that class wasn’t that William Carlos Williams wrote poetry about sex. To me, the real insight was that the speaker, despite his gentle, coy, seductive language of apology, wasn’t really sorry. I suspect most of the boys in class walked out mildly titillated after 20 minutes of talking about sex and poetry, but I walked out with new understanding: straight men are never really sorry.

“I’m sorry, I never meant to hurt anyone.”

As a teacher and school administrator, I got to test a lot of different abstract principles and theories. If you build it, they will come? Only if there’s free food. The truth will set you free? Perhaps, but it also hurts, so you’d better tell the truth with real people in mind. Teenagers, like dogs, can smell fear? Yes, yes they can. Middle schoolers are the worst? No, no they’re not - but people who think middle schoolers are the worst are actually the worst. But one principle got not just tested but proven every day, whether dealing with student concerns, faculty issues, or the all-consuming parent drama (seriously, parents, take the drama out of your children’s schools!): Impact is more important than intent. From the banal to the seriously tragic, “sorry” was never enough, and individuals’ or a community’s capacity to reconcile and move forward depends on each individual’s commitment to understand and address hurtful impact.

The problem with Gruden’s apology, as Ryan Russell highlights, is that it reflects the inaction and performative allyship of the NFL. Instead of exploring the best way to support players and staff when players followed Colin Kaepernick’s example and knelt during the national anthem to protest systemic racism, league leaders and owners fretted about the effects on ticket sales. While they praised Carl Nassib for publicly coming out and promised support, they failed to confront or even consider the toxic culture that stops players from coming out. Gruden’s apology fails to recognize his offense or even squeeze-in a vapid promise to do better or work on himself. He fails to recognize his impact and hides behind his intent.

When it comes to hatred, bad apples fall from rotten trees. In his guest essay, Russell rightly criticizes the NFL for excluding executives and owners (“the real roots of the league’s continuing disappointments”) from moral and professional scrutiny and identifies the necessary next step: “change, inside and out and top to bottom. Every decision - from hiring coaches to signing players to funding and creating social initiatives - needs to be made with the serious and intentional desire to be diverse, inclusive and long-lasting.” The lens that Russell proposes isn’t radical or innovative (it’s what my colleagues and I used to call “mission-driven decisions” and “mission-appropriate hiring”), and it echoes the reality that transformation begins in small, direct, and immediate changes - changes that Gruden and others successfully avoid with words like, “I’m sorry, I never meant to hurt anyone.”

Gruden never intended to hurt anyone. Neither did the bully who slammed me against the wall in ninth grade. He didn’t intend to hurt me - he intended to intimidate me. He intended to maintain the power and privilege that he enjoyed and to show me exactly how he would hold on to it. I wasn’t part of his calculus - I was just an expendable plebe who happened to be on his path - but for over 30 years, I’ve lived with and carried the damage of that moment.

But I’ve also lived with the memory of Mr. Flanagan, who showed me that being a faggot isn’t all doom and gloom. A few years after high school, I learned that a group of gay teachers secretly watched out for queer kids. Because of the strictures of Catholic school-life in those days, they couldn’t do much to explicitly advocate for us, but they found subtle ways to affirm us, lift our spirits, give us some semblance of hope and safety. They lacked the authority to transform the school’s culture, but through their solidarity, they gave us an experience that was better than their own and helped us to love, not fear, ourselves. And Mr. Flanagan, one poem at a time, gave me a life-saving lesson: once in a while, when you read between the lines, you dig up something wonderful.